Board Representation

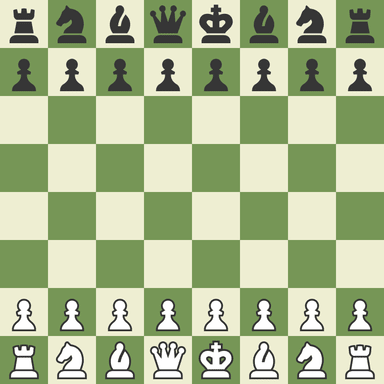

In case you don't know, this is what a chess board looks like:

There are commonly 3 ways a game of chess is programmed. I'll go briefly into the pros and cons of all three methods below.

1. Using a 2D array

Well, when you think of a chess board, it's 8 squares along and 8 squares down, so it makes sense to construct a board like this, right?

[

[ r n b q k b n r ],

[ p p p p p p p p ],

[ . . . . . . . . ],

[ . . . . . . . . ],

[ . . . . . . . . ],

[ . . . . . . . . ],

[ P P P P P P P P ],

[ R N B Q K B N R ]

^

here

]

Say you wanted the square where the king's bishop starts. That can easily be represented by the index: [7][5].

However, accessing multiple arrays and especially copying nested arrays (in the event of constructing a decision tree) is very time-consuming and inefficient.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Intuitive | Slow, since you need to access two arrays |

| Easy to update | Positions are two numbers instead of one |

2. Using a 1D array

This is a bit better than the 2D array approach, now that you reduce the overhead of accessing two arrays, but it can still be improved.

For a start, when calculating things like rook and bishop moves, you can unintentionally go to the other side of the board when checking squares. On the 2D array, you can easily check that x and y (in [x][y] format) don't exceed either 0 or 7:

def check(x: int, y: int) -> bool:

return 0 <= x < 8 and 0 <= y < 8

But for a 1D array, you have to either:

- manually get an

xandyvalue (usingdivmod(n, 8)) and check that way - store an array of edge values (like a mask) so you know when to stop

Either way, we can still do better.

3. Using bitboards [the best approach]

A chess board has 64 squares. Most computers can do incredibly fast and optimised operations on 64-bit numbers. Can you see a correlation?

We can use what's called a bitboard to represent our game state. A bitboard is just a binary number that represents some position (or part of a position) of a game. For example, in Connect Four, you can represent this position:

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

. . . . . . .

. . . 2 . . .

. . 1 1 . . .

. . 2 1 . . .

With two binary numbers to represent the counters of each player:

# Player 1 # Player 2

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . 1 . . .

. . 1 1 . . . . . . . . . .

. . . 1 . . . . . 1 . . . .

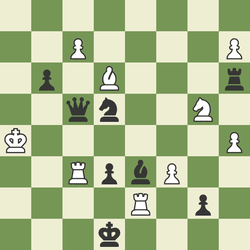

We can do the same with chess. Take this position for example:

A bitboard representing all the pieces on the board could look like this:

. . . . . . . .

. . 1 . . . . 1

. 1 . 1 . . . 1

. . 1 1 . . 1 .

1 . . . . . . 1

. . 1 1 1 1 . .

. . . . 1 . 1 .

. . . 1 . . . .

For context, I'm using what's known as a Little Endian format for my bitboards. The positions of each bit are laid out like this:

56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63

48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55

40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47

32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39

24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7